Famed for their elaborate rituals honouring the dead, a trip to Toraja is an adventure set in the highlands of South Sulawesi. Now through Torajamelo, you can stay in the homes of locals to experience the community’s heart and soul, while supporting their fledgling livelihoods in tourism.

MEET MERI AND THE TORAJANS

When Meri is able to bring a pig to every ceremony in the community nestled in the mountains of Toraja, her hallowed dream will be fulfilled.

One of many weavers living in this region, Meri’s dream echoes that of many in her unusual community, whose culture would strike even seasoned travellers as a world apart.

Elaborate funerals, amongst other rites and rituals, have become the way of life for the 450,000 inhabitants — an indigenous ethnic group also called Toraja — on this land in South Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Pig and water buffalo offerings are the main currency of exchange during these events and a stern label of your social prestige in the community.

The community blends Christian beliefs, as brought in by the Dutch missionaries in the early 1900s, with local religion known as Aluk to Dolo or “Way of the Ancestors”. Living 14,000 feet above ground, this mountain tribe has stuck firmly to its ancient roots, spanning generations.

But in a place where the dead are exalted in grand ceremonies, female empowerment, which has long taken a backseat, has been quietly making inroads. And I was here to see this for myself, even as I took in Toraja’s colourful culture.

#SOULFULTRAVEL

Toraja has long been a magnet for adventurous travellers, but the benefits of tourism has not always trickled down to the community as a whole.

“Most of the tour guides and agents were coming from outside the region, like Bali and Makassar, and the money was not coming back to the community. And with that, the special traditions and stories of this community were also being diluted,” shares Dinny Jusuf, founder of social enterprise Torajamelo.

Determined to do it differently, Dinny, who was already successful in helping women weavers in the Sa’adan region find an international market for their handcrafted products, joined hands with the local Tourism Village Association in Suloara’. Together, they ventured into community-based tourism.

Under this initiative, dubbed #SoulfulTravel, Torajamelo’s weavers and participating villagers earn additional income by renting out their homes and offering tours that may include traditional home cooking and learning the local dance.

Arriving at the village, I am greeted by stunning views of the green, hilly landscape, and the sound of rooster crows and chuckling children in the background. I felt as though I was on the cusp of an adventure in a strange new land, yet in a welcoming embrace that felt like home.

The homestays are simple but cozy, and some are fitted with amenities like western-style toilets. Those seeking a less rustic experience can choose to stay with Dinny at her house, Banua Sarira, at Batutumonga, a villa hugging the mountainsides of Toraja amidst sweeping rice fields.

Less than a year since the venture was made official, Torajamelo is seeing results, with participating Torajans gaining a sense of agency through improved economic circumstances and sense of dignity, especially among the women.

Arriving for my weaving workshop, I was greeted by weavers who were initially reticent, their reserve only dissolving when they demonstrated their skills.

Over coffee and kue, we overcame the language barrier to learn more about each other. I was amazed at how delicately they managed both technique and artistic flair, and how earnestly they passed on these skills to their daughters — who in turn skillfully balance their school work with this traditional art of weaving.

Says Dinny, “The weavers are proud to share their culture with guests from abroad. They find it useful to transfer their skills in communication, financial literacy and leadership skills in this new context. Plus, they can now sell directly to the tourists and earn additional income.”

An ex-banker from Bandung, Dinny’s connection to Toraja is a personal one — her husband is Torajan nobility, whom she met and fell in love with during one of her trips.

Staying with Dinny is akin to staying with a friend: she is happy to engage in conversations under the stars of her second floor verandah, sharing intimate insights into the traditions of the Toraja community.

The key to Torajamelo’s success has been keeping the community at the heart of its mission. “As long as the community remains at the core of this venture, and we keep them involved in all our programmes, we can stay authentic,” says Dinny.

HEAD IN THE CLOUDS

The Toraja landscape boasts scenic mountain views and wobbly roads opening up to rice fields and boat-shaped roofed ancestral houses called tongkonan.

There are no postal codes. Clans still live together in compounds. These houses are built with bamboo and raised from the ground to reduce the impact of frequently-occurring earthquakes in the area.

Rice is the subsistence crop, and the harvested rice is stored in special “rice barns” — carved and painted with traditional motifs like the buffalo or the sun, telling a story through the symbols.

Travelling on an itinerary planned by Torajamelo, I dove into diverse facets of the community. Cultural music and dance performances. Visits to the workshops of the traditional weavers, woodcarvers and coffee planters.

Soft spoken by nature, every person greeted me with a smile and a friendly handshake, locking my attention with gentle gazes as they shared their unique practices. Unlike many other places I have travelled through, there was no touting at any point of the tour — which I was told stems from the proud Toraja culture.

Torajamelo also designs tours according to individual preferences, catering to its diverse spectrum of tourists. The tours have attracted the likes of Indonesia’s Master Chef, William Wongso and film actress, Christine Hakim.

Dinny is working closely with the newly reorganised local tourism board, which has recently set up the Tourism Information Center dedicated to boosting tourism in Toraja in a healthy and harmonious way.

The last thing they want is to attract travellers who are just in Toraja to “tick boxes on their tourist trails, and have no interest in understanding the community or nature”, says Dinny.

AT DEATH’S DOOR

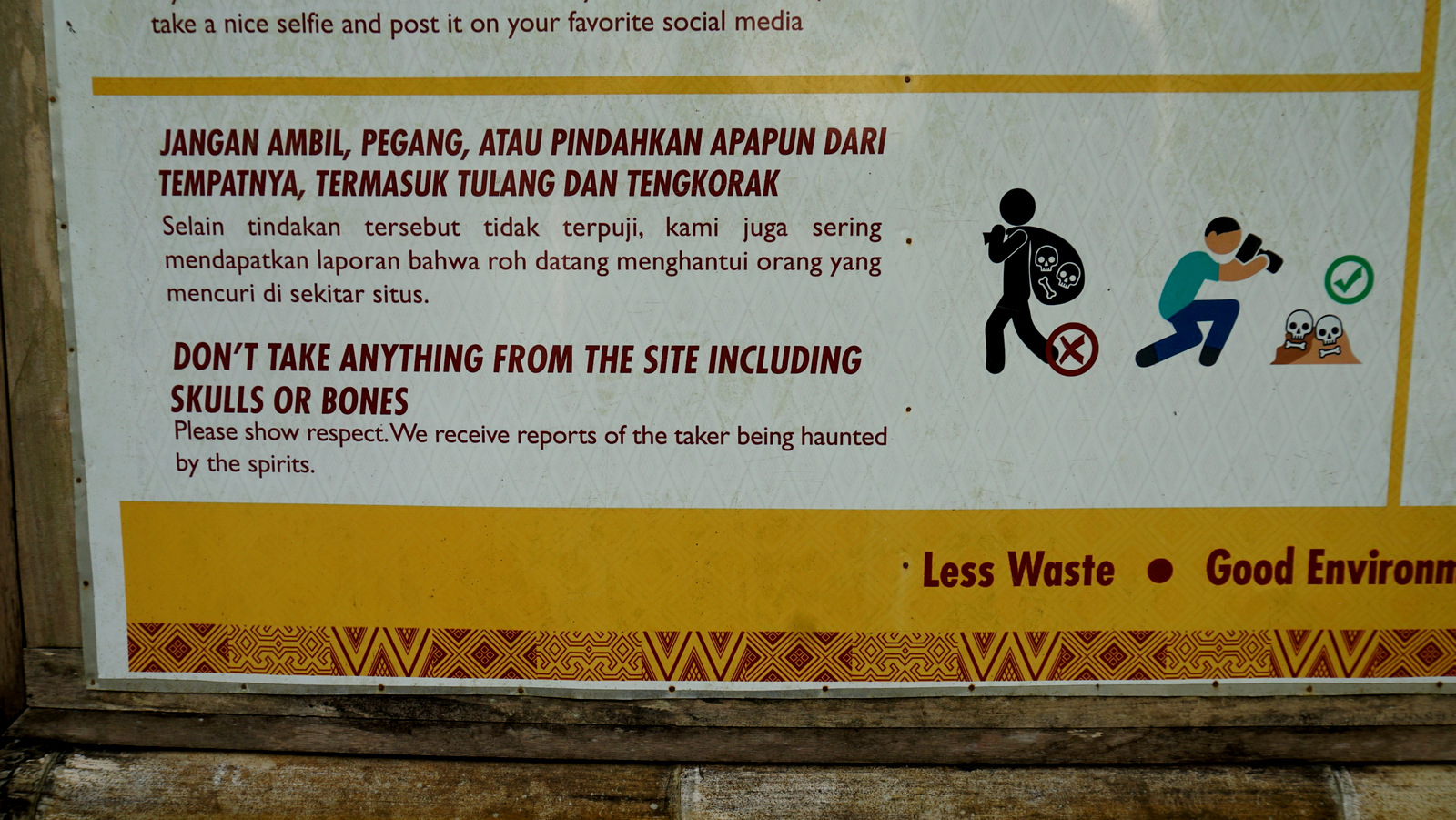

No visit to Toraja is complete without a visit to the local market, and the many graves sites that dot the region and form the centrehold of the community.

Toraja’s death rites are a big draw for travellers, who feverishly take photos as the Torajan go about their business, unperturbed by the attention.

Tipped by Dinny on a funeral gathering nearby, I venture to see this for myself, though not before I am given a primer on the significance behind the elaborate rituals, which can cost anything between US$50,000 to US$500,000.

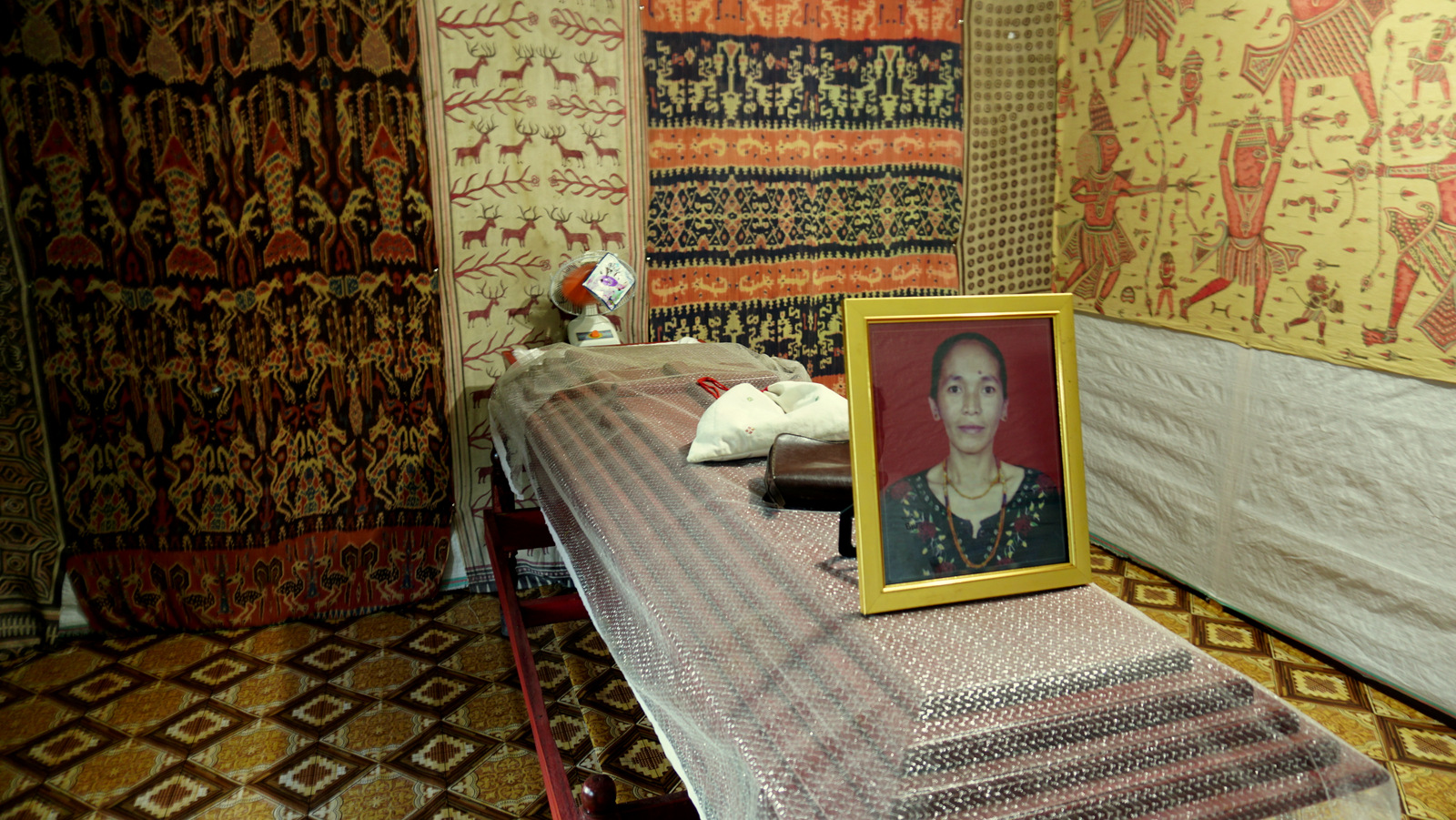

When a Torajan dies, the body is embalmed as funeral preparations can span months as the family saves enough money for the rituals. The funeral, when it happens, can go on for days, with sacrifices of pigs and water buffalos, processions, chanting, dancing and feasting.

The meat from the animals sacrificed is divided among the guests to take home, and the government receives taxes on the animal offerings.

After the funeral, the bodies are buried in stone graves carved into cliff sides, and marked with wooden effigies meant to protect the deceased.

Every few years, families gather to clean the graves, where the dead are taken out of the coffins, washed, and dressed in fresh garb.

After the ceremony, when the sensory overload wore off, I could not help but feel slightly envious. While I grapple with urban existentialist tendencies, here is a community deeply in tune with their ancestors, holding firmly to their belief and values, celebrating life and death in perfect unison.

Not every traveller gets the chance to attend a funeral here, and I consider myself very fortunate. All I can say is, be respectful, be mindful. And always carry a black shirt whilst travelling in Toraja, in case you are invited to a pesta orang mati — a party for the dead.