In Long Mỹ, a village in Vietnam's Mekong Delta region, Phan Thị Nga and her childhood friend, Chiêm Thị Bé, are working on a batch of colourful patchwork cushions destined for customers from as far as Europe.

As they work, Nga recounts a time in Long Mỹ when travelling on xuồng, local-style wooden boats, was a daily occurrence. "We used to bathe and even cook using the river water, now no one would dare do that," she exclaimed with a laugh, referring to the pollution that has swept the waters.

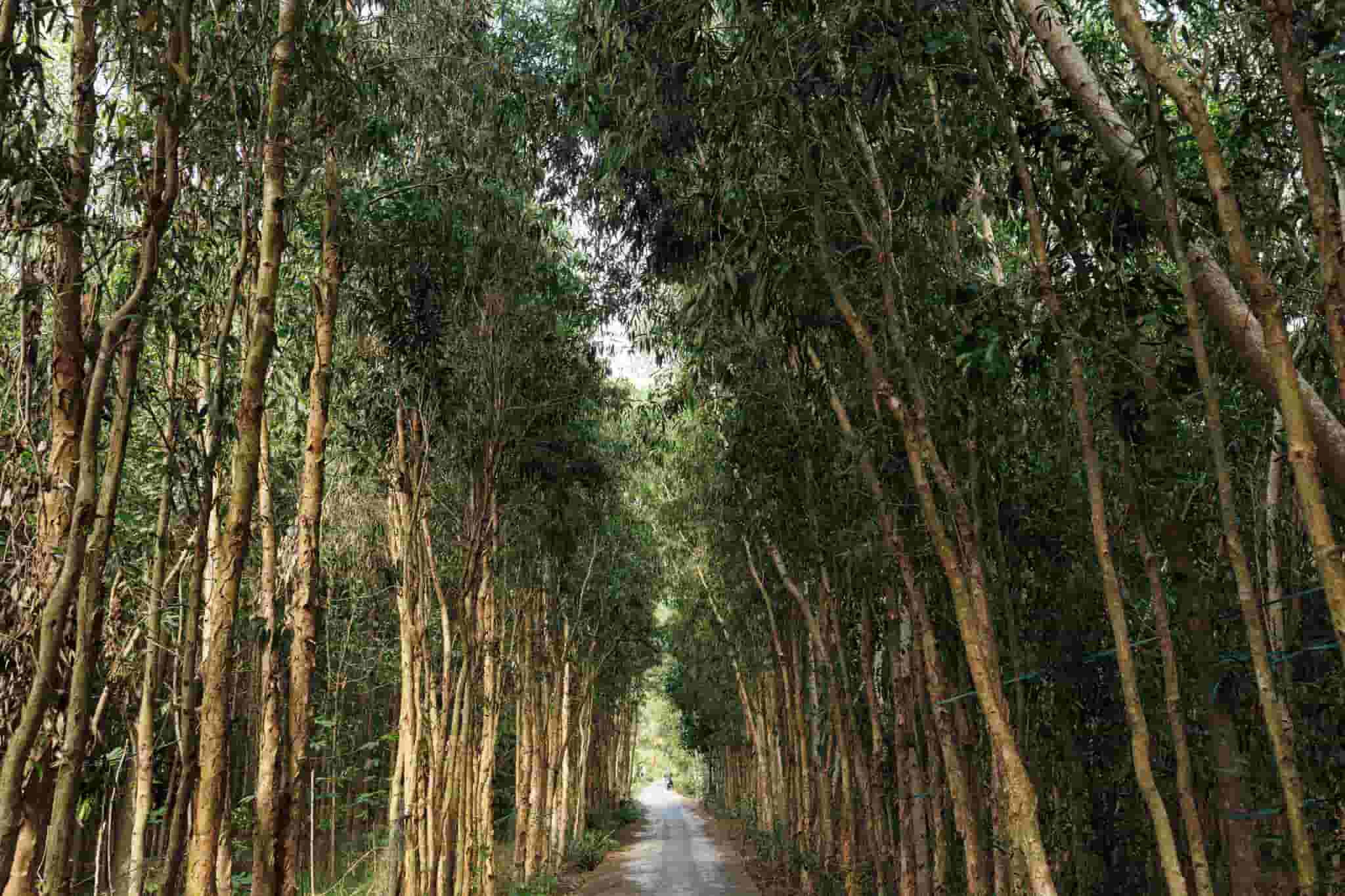

Located in Hậu Giang province, water still flows into Long Mỹ from the grand Mekong itself, forming countless tributaries and streams, flanked by rows of Flame of the Forest trees.

But the picturesque setting hides decades of poverty from casual eyes. As the land becomes less suited for farming owing to unsustainable farming practices and pollution, the flowing streams leave villagers, who cannot afford their own transport, stranded from schools and other services that might lift them out of poverty.

For women like Nga and Bé, crafting quilts for Mekong Quilts, a social enterprise that creates sustainable work for underprivileged women, was a boon to their fortunes — until orders dried up.

The COVID-19 pandemic’s halt on international travel meant the end of demand for the women’s intricate quilts, which were highly popular with travellers.

But sustained by a small stream of online orders and a pivot towards making new products like face masks, Mekong Quilts, which still operates one shop in Ho Chi Minh City, has held onto its mission to uplift the community.

And as travel gradually resumes, Mekong Quilts is now also running cycling tours to the Mekong Delta, where visitors can get to know the communities behind the crafts.

The Women of Mekong Quilts

Nga belongs to the first batch of women trained by a British fabric designer when Mekong Quilts first started in 2001. “[Partly] because I love the job, and because of my previous experience as a seamstress,” Nga says, recounting how she came to join Mekong Quilts.

“Many [of the ladies] saw me making quilts and asked to join and learn the craft!”

Extremely passionate about quilting, she explains the labour-intensive process: "We soak the fabric [in soap water] for one day before drying for another day. After that, we iron all the pieces of cloth to make sure the patterns are well-aligned.”

Larger details are then completed using sewing machines, with smaller details and patchwork finished painstakingly by hand.

"Once [the quilts are] finished, we wash them one more time!" says Nga, who is now the leader of Mekong Quilts sewing team in Long Mỹ village’s Thuận An ward. She hopes that demand recovers as the pandemic dies down.

Adds Bé: “Quilting work gives us stable work. It also gives us voice in the household. Without it, many of us [women] would need to go to Saigon to work.” She notes that it would also be “very difficult for kids to stay in school”, as they may need work to support their families.

The Fabric of Life

For poorer families in the region, traversing 'monkey bridges’, or cầu khỉ, as the locals call them, is an everyday ordeal. Life without a motorbike may mean being trapped in a never-ending cycle of poverty.

In 1994, when Bernard Kervyn founded NGO Mekong Plus — the parent organisation of Mekong Quilts — funding the cost of building better roads and bridges was top on the list of priorities.

"Accessibility means children can go to school and stay in school," says Bernard, who worked in the human rights sector before starting Mekong Plus.

Mekong Plus offered to fund up to one-third of the cost of construction, but early efforts were stymied by a lack of support from local authorities. “We finally arrived in Long Mỹ, and established a long term working relationship with Ánh Dương centre, an independent NGO that shared similar ideals,” shares Bernard. Since the 1990s, Mekong Plus has helped construct at least 10 to 20 bridges and about 20km of rural roads annually.

Then came Mekong Quilts, which was started as a social enterprise to create employment for local women. “Providing the mothers with work means the children can stay in school,” Bernard notes.

So far, over 150 women from the Mekong Delta have been engaged as artisans, who are paid for each item they create — a product range that before COVID-19 included festive papier-mâché hangables to water hyacinth fibre tote bags. Mekong Quilts was such a success that the social enterprise was able to open five shops in Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi, Hôi An, Siem Reap and Phnom Penh.

An Ecosystem for Empowerment

Before the pandemic, Mekong Quilts was able to fund a scholarship programme with its proceeds. Due to the Mekong Delta’s remote and difficult terrain, distance and the affordability of basic transport can be hurdles to a child's education. “The average cost of keeping a child [from the Mekong Delta] in high school is almost VND12,000,000 (US$530) a year,” Bernard notes.

The scholarship programme has helped the families of youth like Nguyễn Văn Huynh, who is now working remotely for a European company; his sister Nguyễn Thị Huỳnh Như has managed to continue her schooling.

Mekong Quilts was also able to modestly contribute to Mekong Plus which runs programmes to improve access to healthcare, education and microfinance opportunities for underprivileged communities in the Mekong Delta. For example, the micro-credit schemes help locals to start small-scale pig, eel, duck egg and even straw mushroom farming projects.

‘Brother’ Phạm Thanh Trần, one of Ánh Dương's farming experts, describes how locals with little land can farm straw mushrooms for a quick turnover. A single stash of straw can produce up to US$30 worth of mushrooms a month, using less than a sqm worth of space.

A Ride to the Finish Line

As the pandemic worsened, Mekong Quilts’ quick-thinking team, not willing to simply wait for work to dry up, were able to launch a line of hand-sewn triple-layer fabric masks with eye-catching designs, several of which feature traditional batik and Hmong indigo fabric acquired sustainably from tribeswomen.

The masks helped keep the artisans employed as quilt orders dropped 60 per cent by June 2020. "We began focusing on baby quilts, cushions and also, fashion," Hồ Tiêu Đan, a long-time volunteer, added.

Although less than half of Mekong Quilts’ pre-pandemic headcount of artisans remain working regularly, the social enterprise has managed to stay afloat.

“We make about 1,000 masks every month [now],” shares Út. “Many of us have returned to working in big factories or in the fields but at least there’s still work to do.”

Meanwhile, Mekong Quilts’ bamboo bicycles are finding a growing audience.

Designed by Bernard with Alain Kit, a French bicycle designer, the bicycle takes advantage of the abundance of bamboo in Vietnam. “Except for the wheels, tyres and joints reinforced by hemp fibre and epoxy, the bicycles are fully bamboo!” Bernard says with pride.

At its peak, Mekong Quilts’ bamboo bicycle workshop kept nearly 20 craftsmen and women employed. Currently, only four remain, as the pandemic has driven down demand.

In the last few months however, cycling tours — when allowed by the authorities — on these bikes have helped to support Mekong Plus. Cyclists can visit Long Mỹ over a two-day trip where they see a side of Vietnam that is often overlooked amid the rapid transformation of the country.

First organised in 2014 for donors of Mekong Plus, the trips have become popular since Mekong Quilts opened them to the public, generating some US$2,780 in the first six months after tours were allowed to resume. “[Beyond travelling costs], participants contribute freely to Mekong Quilts at the end of the tours, largely going back into our scholarship programme,” Bernard says.

Tours aside, Mekong Quilts hopes that more people are inspired by the beauty and the stories behind its crafts to make a purchase, while looking forward to Vietnam opening the door to international tourism, allowing more artisans to be employed. As volunteer Đan puts it: “It’s a gift that gives twice.