Meet Sanju

For Sanju Negi, life has come full circle.

From opposing the creation of a national park in the western Himalayas — on grounds that it would destroy locals’ ability to live off the land as they have traditionally — Sanju is now a custodian of the park’s natural environment.

First, recognising the potential of eco-tourism, he became a trekking guide and member of a cooperative committed to responsible tourism in partnership with Himalayan Ecotourism, a travel social enterprise.

Now, with tourism income drastically fallen as a result of COVID-19, Sanju has joined hands with Himalayan Ecotourism to tap the power of carbon offsetting: allowing people all over the world to offset their carbon footprint by planting trees in the Himalayas.

The road to empowerment

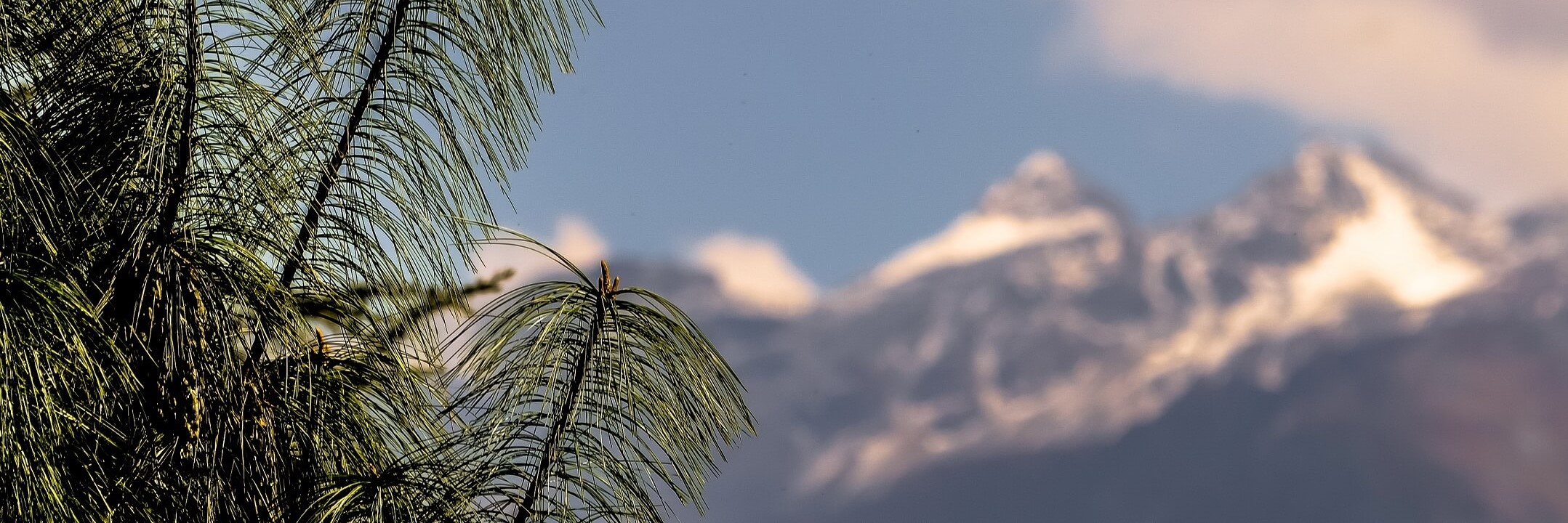

With its never-ending pine and cedar forests, flowing streams and waterfalls, and snow-capped peaks rising grandly above it all, Tirthan Valley, which is part of the Great Himalayan National Park (GHNP), is the postcard-perfect destination travellers dream of.

Himalayan Ecotourism grew out of a desire to divert the benefits of tourism towards the valley’s communities, for whom the creation of the park in 1984 had signalled loss.

Many villagers had depended on the medicinal herbs and forest produce they foraged as a source of income, while the land was also important grazing ground livestock. “As locals, many of us were opposed to the national park because it cut off our right to the forest and our livelihood had depended on it,” says Sanju.

With tourism taking off in the region, Stephan Marchal, a Belgian who had worked on sustainable development projects in India, hatched the idea of an ecotourism cooperative owned and managed by locals.

In 2014, he co-founded Himalayan Ecotourism, a joint venture with the GHNP Community-Based Ecotourism Cooperative, which comprises local guides who are also shareholders. Stephan handles management and marketing needs, while guides like Sanju — who is also the treasurer of the cooperative — take turns to lead treks, from which they keep 60 per cent of the revenue.

“I was opposed to the model of ecotourism where locals are mere daily wage labourers while the business was owned by somebody else. From the beginning I was sure I wanted to develop and grow the business in the right way,” says Stephan.

Himalayan Ecotourism’s philosophy of inclusion, not exclusion, also extends to its guests. While the conventional image of trekking is one of outdoor gear ads filled with lean and fit-looking individuals, Himalayan Ecotourism also organises trips for guests with mobility problems, such as older hikers or people with disabilities.

The trips range from forest bathing — camping in the wild and immersing oneself in nature — to nine-day treks, aided by equipment and specially-trained guides to ensure comfort and safety.

In 2019, Himalayan Ecotourism won not one but two of the Indian Responsible Tourism Awards instituted by Outlook Responsible Tourism.

An unexpected turn

In early 2020, COVID-19 began its sweep around the world, bringing global travel to a halt and devastating communities that had depended on tourism for their livelihoods.

Himalayan Ecotourism was not spared, with business plunging to zero overnight. “We had to find alternate sources of income for our cooperative members,” shares Stephan.

The response was one that would not only provide relief income to its members, but also expand on its eco ethos: a reforestation programme implemented by members which would repair land damaged by overgrazing, logging, and fires, supported by anyone who wishes to offset their carbon footprint.

For example, someone making a return trip between Paris and Delhi by air will incur around 1,680kg in carbon emissions. To offset this, three trees will need to be planted and maintained for 40 years (Himalayan Ecotourism’s calculations are based on a tree removing an average of 15kg of carbon emissions from the air annually over 40 years).

Through Himalayan Ecotourism, individuals can buy carbon credits, the proceeds of which will be used to plant and maintain the trees for a minimum of 20 years. Customers will be given periodic updates, including geotag-enabled reports.