Photo by Malika Virdi

“It’s not just about how much we can earn, but also about being able to share our dukh-sukh (sorrows-joys).” - Kamla Pandey, homestay host

As Kamla Pandey tells me this over a WhatsApp call, I could picture her in warm layers wrapped over her sari, as the winter sun bathed her house through its large glass window.

Just a couple of hours ago, the sun would have risen over the five snow-clad Panchachuli peaks, casting an otherworldly glow over the remote mountain village of Sarmoli. The village sits in Uttarakhand’s Munsiari district, close to the borders of Tibet and Nepal in the Greater Himalayan region, an 11-hour drive from the nearest airport and train station.

It was over many such mornings, way back in 2016, that I first got to know Kamla. Like many women in Sarmoli – and the neighbouring villages of Shankhdhura and Nanasem – she runs a homestay as part of Himalayan Ark, a community-owned social enterprise committed to responsible, purpose-driven travel in the region.

When COVID-19 decimated tourism incomes across the world, Himalayan Ark shifted its focus from tourism to digital upskilling, reviving traditional crafts and long-term food security.

As we chatted over the phone about the threat of the Omicron variant, Kamla confessed that yes, the pandemic came as a big jhatka (shock). But as a community that has been together through many storms over the years, they continue to sail together, no matter which way the winds blow.

Homestays seeded in conservation

Photo by Malika Virdi

Kamla didn’t always have the confidence — or the opportunity — to host strangers from around the world in her home.

In fact, back in 1992, when avid mountaineer Malika Virdi moved to Sarmoli, the only livelihood opportunities available to women were meagre earnings from agriculture, or demanding daily wage labour at construction sites.

About a decade later, when Malika was elected sarpanch (head) of the van panchayat — a 70-year-old village institution for the sustainable management of forests — she set out to change this, by connecting conservations and livelihoods.

“The use of the forest needed to be regulated, but why would anyone be interested in conserving something they were so desperately dependent on [for fuel and fodder]?” recalls Malika in a recent conversation over a video call.

The proposed alternative: a nature-based tourism initiative that became the foundation of Himalayan Ark. Himalayan Ark would assist members in accessing tourism-linked incomes, and they would commit to participating in local conservation work like planting, maintenance and safeguarding of the land.

The homes of Himalayan Ark’s members became a vehicle for empowerment when they started hosting travellers. Photo by E Theophilus

Back in 2004, only 13 out of 300 van panchayat rights holders signed up, including Kamla. “People were sceptical as to why someone would choose to stay in our village over the hotels in the bustling Munsiari bazaar,” Kamla had told me when we first met.

Global and domestic visitors however, quickly became drawn to Sarmoli, both as a base for high-altitude treks in the Kumaon Himalayas, as well as for volunteer tourism, student trips and slow travel.

By 2019, Himalayan Ark’s network had grown to 20 women-led homestays, managed by a roster system where priority is given to those who have no alternate source of income. Twenty-five guides had been intensively trained in birding, high-altitude trekking and natural history, of which over half are women. Having travelled extensively in India, that is a statistic I constantly marvel at, for Sarmoli is one of the only places in the country where I have hiked with a female high-altitude guide.

A community that celebrates its cultures

A feast for the eyes and the appetite on Ghee Tyohaar, an Uttarakhand festival. Photo by Trilok Singh Rana

What first drew me to Sarmoli though, was not its equitable tourism model but Himal Kalasutra, a mountain festival for the locals (not tourists, though they are welcome to join). People from villages across the Gori Valley come together to go bird watching, learn outdoor activities like yoga or ultimate frisbee, and get a sneak peek into digital tools like Wikipedia.

I joined a bird watching excursion amidst oak and deodar forests bursting with blooming red rhododendrons, participated in a yoga session in the surreal backdrop of snow and mist clad mountains, and cheered on locals as they set out on a high altitude marathon to Khaliya Top, a spectacular alpine meadow at an altitude of 3,500m (an altitude gain of 8,000 feet over 20km) — best hiked slowly by city folk like me.

Photo courtesy of Himalayan Ark

Inspired by the festivities, I offered an impromptu Instagram tutorial to young adults from Sarmoli and Shankhdhura – which led to the creation of @voicesofmunsiari, India’s first Instagram channel to be run entirely by a rural village community. In 2017, with smartphones crowdsourced via my blog, an Instagram and photography workshop became part of the official festival line-up.

Later, I learnt that in true spirit of community ownership, Himalayan Ark’s homestay hosts keep 80 per cent of the revenue, and voluntarily contribute 5 per cent towards community development — 2 per cent goes to the van panchayat, while 3 per cent goes to a fund that offers interest-free loans for community members to upgrade their homestays.

Over the years, guests have also volunteered their skills to help Himalayan Ark grow, sharing their knowledge in mapping local geography, environmental issues, women’s rights and rural tourism development. “They get an insider's view of community life in the Himalayan mountains and also end up making lifelong friends,” shares Malika.

A return to tradition, an eye on the future

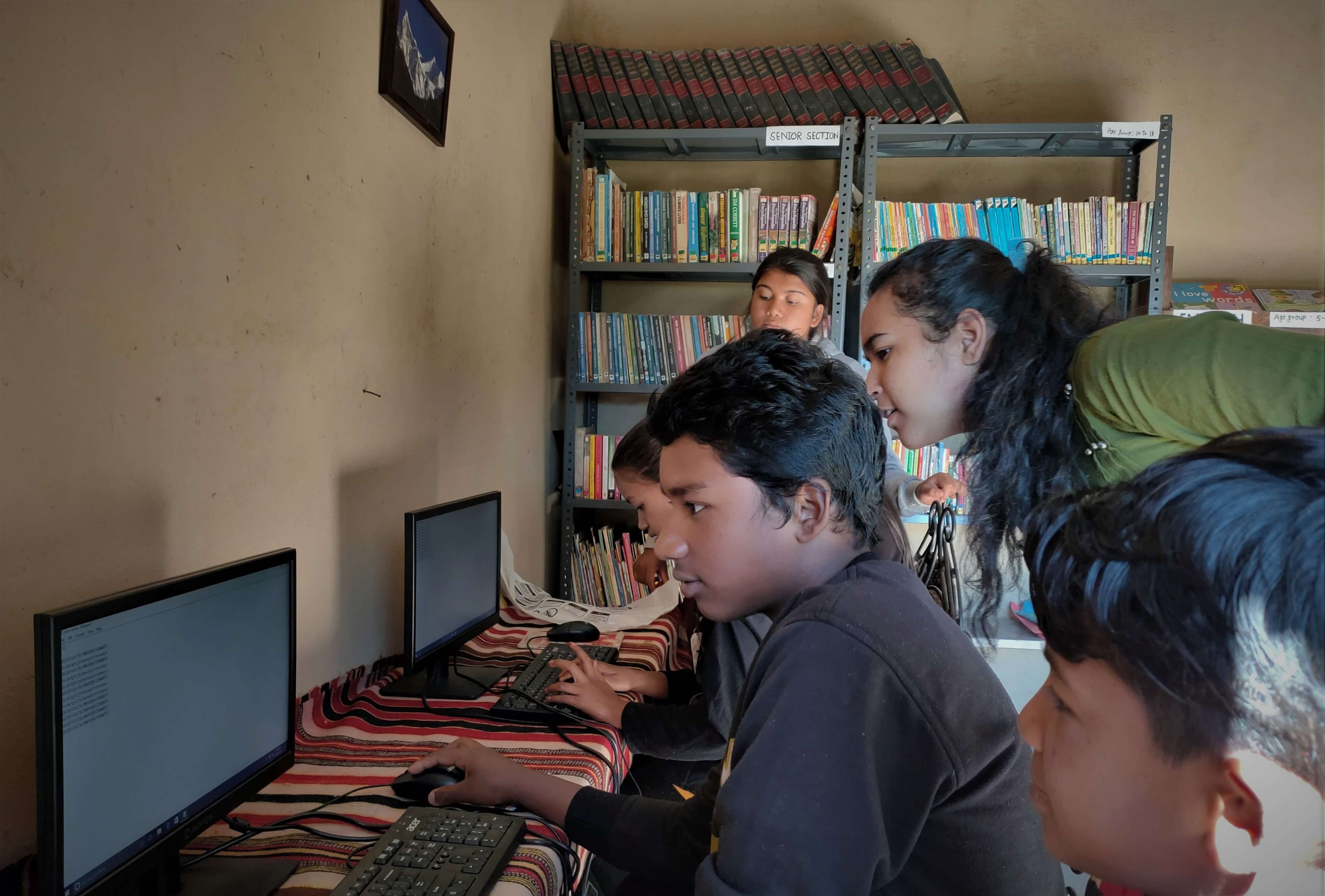

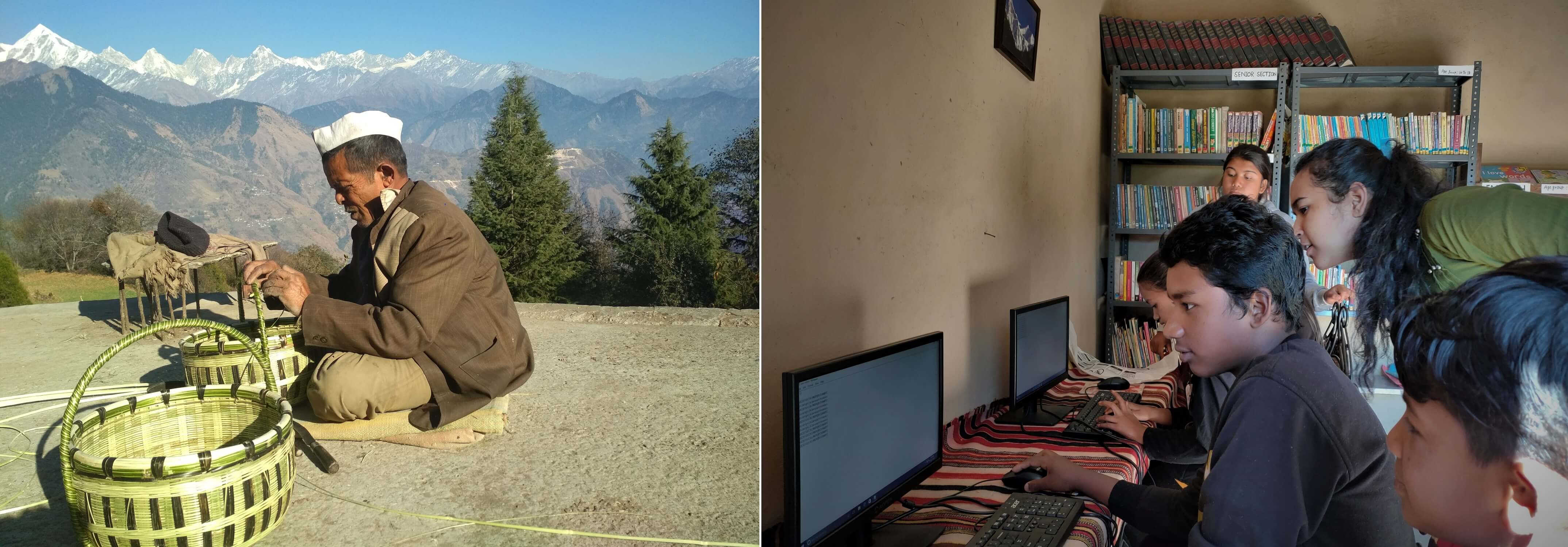

[From left to right] Master craftsman Nain Ram demonstrates how to weave bamboo; Children keep up with school in the digital resource centre opened by Himalayan Ark. Photos by Trilok Singh Rana (left) and Kaushalya Arya

COVID-19 spared the remote mountain villages of Munsiari the worst of the pandemic, but took away their primary source of livelihoods.

“Tourism was all about sharing our rural lifestyle with travellers,” says Malika. “The pandemic left us with no tourism, but we still had our rural lifestyle.”

After the initial shock, Himal Prakriti, the non-profit arm of Himalayan Ark, quickly pivoted into developing alternate sources of income for the community, powered by CSR funding and individual donations.

With a renewed focus on agriculture and food security, some homestay owners and guides were trained and paid to build hoop houses — small, predator-proof greenhouses made with locally available galvanised iron pipes. “We’ve set up vegetable and forest nurseries, and distributed seeds like capsicum, cucumber, fenugreek and broccoli,” Kamla tells me excitedly.

Villagers building hoop houses to increase food security. Photo by Kamla Pandey

So far, Himal Prakriti has been able to reach 100 to 150 economically-depressed farmers across the Gori Valley, many of whom are women.

It then shifted gears towards reviving crafts lost to time, starting with a workshop on likhai – intricate hand-carving on walnut wood, a skill once possessed only by the men of the Ohri community. Until a few decades ago, homes across Kumaon were fitted with likhai-adorned doors and windows, but as demand for traditional houses fell, many artisans gave up their craft.

By the end of the workshop, participants were able to retrofit their homestays with self-carved mirror and window frames.

Abandoned homes with likhai frames (left). Villagers in Munsiari tried their hand at reviving the craft by learning from artisans. Photos by E Theophilus (left) and Malika Virdi

Similarly, members of the community spent time relearning the backstrap loom – a simple concoction made with ropes, sticks and a strap, worn around the waist – once central to the Bhotiya people as they roamed the mountains with their herds.

Reviving these crafts not only created a sense of ownership, community and pride, it also enabled the members to create products for sale through the @voicesofmunsiari Instagram channel.

The focus on rural life did not neglect the need to stay connected to urban demands. As schools shut and lessons moved online, Himalayan Ark decided to convert a planned café space into a digital resource centre. Children who did not have access to smartphones or laptops were still able to attend online classes and study in a socially-distanced setting.

Gearing up for the “new normal”

Photo by Malika Virdi

The pandemic exposed a gaping urban-rural digital divide — and with the interest in travel returning, bridging it remains crucial, so that the Himalayan Ark community can grow their business.

Over the past five years, Himalayan Ark community members, despite not having the social media savvy of more privileged peers, have been sharing glimpses of their lives through @voicesofmunsiari.

Encouraged by their pursuit, Malika and I, together with Osama Manzar of the Digital Empowerment Foundation, co-founded Voices of Rural India — a curated platform for homestay hosts, guides and other community members, to share their stories in their own voices, while building digital storytelling skills and earning an income through digital publishing. One of the first stories published was written by Kamla.

When Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee, an elite Indian university, broached the idea of documenting traditional crafts in the region, two women from the community led the multimedia documentation. Among them was Bina Nitwal from a Bhotiya family, who, armed with her smartphone, interviewed her elders across the valley about the history of the backstrap loom that she herself is re-learning to use.

Mohini demonstrates how to use a backstrap loom to weave textiles. Photo by Bina Nitwal

In the new “normal,” we have no idea what the pandemic (and climate change) might throw at us. But one thing is for sure: the community in Munsiari, held together by Himalayan Ark, will continue to sail towards new horizons.

“Our goal has always been to forge a deep rishta (relationship), both within the community, and of the community with the landscape,” Malika told me. In the face of market forces and looming uncertainties, it’ll be more important than ever.